This week was a short one: Friday was San José (Saint Joseph), Father’s Day and national holiday in Spain.

It sort of makes sense that we wouldn’t work. After all, he’s the patron saint of all carpenters (including boatbuilders). For sure Noah would have been a much better choice, since he was an actual shipwright (Medieval depictions of him building the ark offer a wonderful representation of the tools of the trade, which haven’t changed much since then).

But Noah was not so lucky, having made the mistake of being born before the coming of Christ. He was friend with God and saved all humanity (plus the animals, obv), but he was not a Christian and therefore is spending the rest of times in Hell. Probably forever fairing a hull that will never be fair, or sanding something for eternity… I could not thing of a more terrible torture.

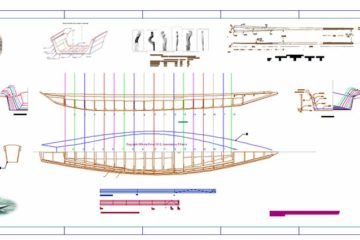

Anyways, let’s not dwell on theology, we have a boat to build!

This week Ioanna has finished planing the after filler block, so that the side planks arrive nice and snug, hopefully without letting water in.

We have also cut both sheer planks at the desired width (around 20/25cm), drilled out some nasty knots and plugged them, and painted the inside with a first coat of primer. It is much easier to do it now then after they will be hanged, with all those frames installed.

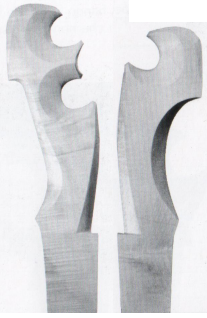

I have spent quite a lot of time trying to figure out the shape of the plank at the bow, and how they meet with the stem.

After some trial and error, and a few phone calls and pictures sent to a boatbuilder in Venice friend of mine, I have come to the conclusion that:

- the stem was set at the wrong height;

- the rabbet I had cut was not quite in the right position.

Also, as a bonus, I had forgotten that the edge of the plank should be cut at an angle inferior to 90°, so that it gets trapped into the stem.

Long story short: on Thursday I took off stem and forward filler block, and milled up a new one. I will be installing it next week.

This is what happens when you have never built a boat of this kind before and you don’t have a boat to copy near to you to use as reference. But it’s probably what makes it more fun. Maybe.

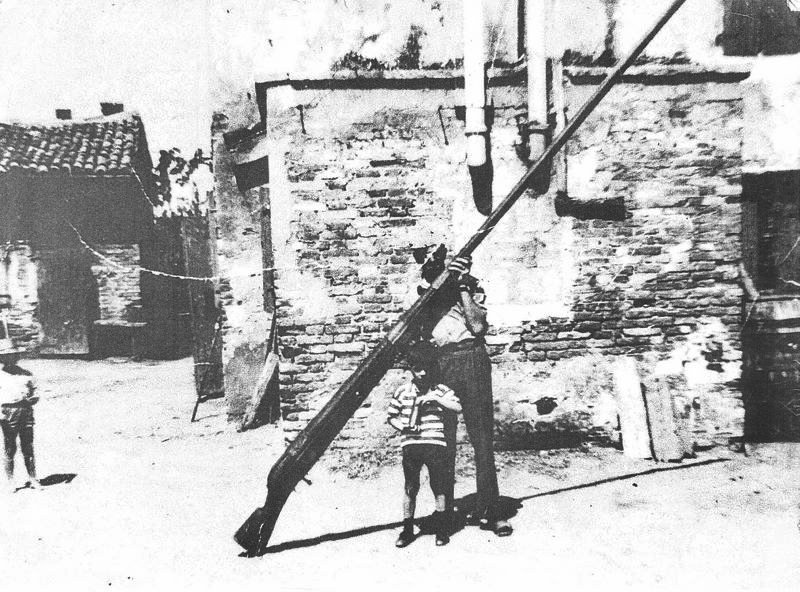

On a more light note, if you follow my stories on Instagram (@acqua_stanca) you already saw our new mascot, that Ioanna (@io_moutu) bought: a miniature decoy duck. The full-sized ones are called stampi in Venetian and were used when hunting in the lagoon of Venice. The boat is a s’ciopon, after all.

Next week we’ll have a press conference to present the project to the local newspapers, let’s hope we have something nice to show them!